INDEX

1. Normans

2. England and Anglo-Saxon

3. King Edward the Confessor

4. William the Conqueror or the Bastard

5. Norman Conquest and Battle of Hastings

6. After the Conquest: Domesday Book

7. Norman Conquest and Brexit

Normans

Normans were the people who settled in northern France since around 900 C.E. The region they lived is now called Normandy, which was named after them. Their name, Norman, means “Northman” as their ancestors (Viking) came from the Scandinavian area. The first Viking to settle in northern France was Rollo, whom King of Francia Charles III ceded the land to due to the frequent pillaging1. Normans were quickly adapted to the new environment. They began to wear French clothes and armor, speak French, marry local French girls, and convert to Christianity2. The cultural mixture between French and Norse resulted in unique, warrior-spirited Norman.

http://www.kendallredburn.com/images/costumesofallnations/IMG_5892.JPG.

England and Anglo-Saxon

Before the Norman Conquest, Anglo-Saxon lived in England. Anglo-Saxons are the descendants of three different Germanic tribes: Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. All of them formerly lived in today Denmark and Holstein. When they were hired by indigenous Celtic rulers as a mercenary, they betrayed their employer and took the land instead. As Germanic tribes, they spoke a Germanic language and believed Germanic paganism. Then inspired by several priests including Aldhelm of Malmesbury and Boniface of Hampshire, Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity3. Despite their conversion to Christianity as they settled in England, their cultural group was distinctly Norse. After the Anglo-Saxon invasion, England was divided into Seven Kingdoms–which also gave an inspiration to famous book and TV show series, Game of Throne. Unfortunate to Anglo-Saxons, Viking Norse decided to raid and invade England as their previous neighbor forsake the Germanic paganism4. Without King Alfred, Anglo-Saxons could have ended up in the same situation as their former loser, Celtic tribes. Under King Alfred of Wessex (ruled 871-99), Anglo-Saxons defeated invaders, and Seven Kingdoms were united thus creating the national unity of England5. The line of King Alfred the Great did not last long. After his death, Cnut (King of Denmark) successfully invaded England, and William the Bastard (Duke of Normandy) also conquered Anglo-Saxon England6. Although Anglo-Saxons were ruled by Norman lords after William’s conquest, their culture and language integrated with Norman. Today, Anglo-Saxons are living throughout the world and are considered as privileged.

Kretschmer, Albert and Rohrbach, Carl. The Costume of All Nations. Plate 22. 1882.

http://www.kendallredburn.com/images/costumesofallnations/IMG_5882.JPG

King Edward the Confessor

King Edward the Confessor was the last King of England as a member of the House of Wessex, from which King Alfred the Great arose. He was the son of Ethelred and Emma7. Due to the Danish invasion, his family was in the exile in Normandy, where King Edward lived his childhood8. Before King Edward rose to the throne, Danes ruled England. Historians estimate that during their reign, Danish kings took about a quarter of million pounds from Anglo-Saxon people9. Under such exploits, when Earl Godwine, Leofric, and Siward decided to install Edward as a King, people welcomed their new Anglo-Saxon King10. However, despite Edward’s marriage with the daughter of Earl Godwine, the conflict of power between Godwine and Edward intensified11. Though it can be seen as a typical power struggle between the king and its vassal lords, Edward’s case ended in a unique situation. When King Edward died without any heir, Harold Godwinson (Earl Godwine) claimed that King Edward requested him to be the next king in the deathbed12. In fact, people during the times of King Harold questioned his legitimacy. Harold Godwinson also stayed in William of Normandy’s court, where he is believed to make an oath to William of Normandy. William of Poitiers (different from William of Normandy) criticized Harold’s action as illegitimate and for making “sacrosanct oath”13. Of course, as Duke William of Normandy and King Harald of Norway both claimed the throne of England, inheritance war began.

William the Conqueror or the Bastard

Before the Norman Conquest, William of Normandy had the nickname ‘the Bastard’. Due to his title as a Duke of Normandy, he was also called William of Normandy. His nickname ‘the Bastard’ came because of the low status of his mother. He was the son of Duke Robert I of Normandy and Herleve, daughter of a tanner14. Due to his mother’s status, when his father perished in 1035, his relatives objected him being the Duke of Normandy15. Though being the bastard, Duke William of Normandy managed to take England with two justifications. First was that King Edward the Confessor promised him to be an heir to England crown, which Archbishop Robert of Canterbury evidenced16. The second was more targeted to Harold. As William of Poitiers explained in his book Gesta, Harold committed perjury when he “ensured that the English monarchy should be pledged to [William of Normandy] after Edward’s death”17. Even the Pope, who held the authority over feudal countries, supported William’s legitimacy18. Such claims were significant in the Medieval Age. With the legitimate claims, William could justify his conquest and gain support from the local population.

Norman Conquest and Battle of Hastings

Duke William of Normandy decided to take the crown by himself. He then prepared the invasion to England through Dover channel. He planned to land on the Kent then march toward London19. Fortunate to William, King Harold Godwinson faced another threat from North, where his brother Tostig allied with King Harold Hardrada of Norway landed to take the crown20. Two-side war is always risky as the army will be divided into two. King Harold Godwinson had to face William’s Normans in the south and King Harold Hardrada’s Vikings in the north. English King first fought against Vikings at Stamford Bridge in January 106621. The battle ended in favor of England, with the deaths of both Tostig and King Harold of Denmark22. Yet, Harold Godwinson still had a threat of William the Bastard. After the forced march, Harold’s exhausted army reached Senlac (near Hastings) and fought on 14 October 106623. The Battle was not in favor of William until Harold was suddenly killed by a blind arrow and a Norman knight24. Anglo-Saxons were defeated, and William the Conqueror marched to London. On Christmas day in 1066, Archbishop Ealdred of York crowned William the Conqueror, and witenagemot (council of nobles) declared Godwine an outlaw25 26. Thereby, England was under William the Conqueror’s hand. The problem for William was to rule the newly conquered lands, which was much bigger than his lands in Normandy.

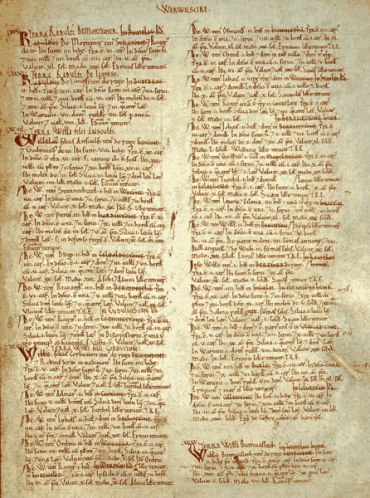

After the Conquest: Domesday Book

William knew the difficulty of ruling the conquered lands. Especially, due to the local resistance to foreign rulers, William as a Norman would have much more trouble than Anglo-Saxon rulers. The justification for his conquest was one thing that would help his reign. Another was to install Norman lords throughout the lands of England. Not only will he be able to give a reward to his vassals, but those Normans will support him, unlike Anglo-Saxons. So, William built about 80 castles in strategic areas27. He also confiscated the lands of Anglo-Saxon lords and distributed to Norman knights, thus prompting Norman French to be the language of English court 28 29. In December 1085, Domesday Book was published under the commission of William the Conqueror30. The surveyance of available farmland is mandatory for any countries. William probably knew this. With an accurate documentation of lands, William could collect a tax, manage the population, conscript army, and install feudal lords friendly to him.

Norman Conquest and Brexit

Norman Conquest is a significant event in the history of England. It determined the next 300 years of England. Previous to Norman Conquest, England was included in the Oceanic power, which is a set of countries focusing more on the ocean and naval force. Due to frequent Viking raiders and invasions, Anglo-Saxons paid attention to Scandinavian instead of France. However, after the Norman Conquest, English nobles who also held their land in Continent (i.e. France) kept their eyes on the Continent rather than the ocean–i.e. Vikings. They utilized inheritance to expand their lands on the Continent and actually succeeded. By the times of Hundred Years War, England held lands in France ranging from Gascony to Burgundy31. This subtle form of invasion angered Franch king. Eventually, England and France fought over the inheritance of France crown and Britanny32. The Hundred Years War resulted in the separation of England from the Continent. However, until then, Norman Conquest shifted England from Oceanic to Continent.

Brexit is the event that United Kingdom (i.e. British isles) tried to break itself away from European Union (EU). It began on June 23, 2018, when voting for the Brexit favored the side who wants to leave EU33. I interpreted this event as another shift of Britain from Continent to Oceanic. Previous to the Brexit, UK was in the middle of Continent and Oceanic, each represented by EU and USA. If UK leaves the EU, who will the UK find as their friend? It should be USA who can be UK’s alliance. That is why Brexit resembles Norman Conquest though it was through voting and people’s voice instead of military conquest. While Norman Conquest shifted England from Oceanic to Continent, UK shifted itself from Continent to Oceanic by Brexit.

Footnotes

1. “Normans.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015.

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

2. Robinson, Mark. “How the Normans changed the history of Europe.” Youtube, uploaded TED-Ed, 9 August 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Owf5Uq4oFps. Accessed 4 Dec. 2018.

3. Orchard, Andy. “The World of Anglo-Saxon England.” A Companion to Medieval Poetry, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, pp. 18.

4. Orchard, Andy. “The World of Anglo-Saxon England.” A Companion to Medieval Poetry, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, pp. 16.

5. Orchard, Andy. “The World of Anglo-Saxon England.” A Companion to Medieval Poetry, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, pp. 24.

6. Orchard, Andy. “The World of Anglo-Saxon England.” A Companion to Medieval Poetry, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, pp. 29.

7. “Edward III ‘The Confessor’ (r. 1042-1066)” The Royal Family. Accessed 26 November 2018.

8. “Edward III ‘The Confessor’ (r. 1042-1066)” The Royal Family. Accessed 26 November 2018.

9. Eric, John. “Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession.” The English Historical Review., vol. 94, no. 371, 1979, pp. 242-3.

10. Eric, John. “Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession.” The English Historical Review., vol. 94, no. 371, 1979, pp. 243.

11. Eric, John. “Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession.” The English Historical Review., vol. 94, no. 371, 1979, pp. 245.

12. Winkler, Emily A. “The Norman Conquest of the Classical Past: William of Poitiers, Language and History.” Journal of Medieval History, vol. 42, no. 4, 2016, pp. 459.

13. Winkler, Emily A. “The Norman Conquest of the Classical Past: William of Poitiers, Language and History.” Journal of Medieval History, vol. 42, no. 4, 2016, pp. 473.

14. “William I ‘The Conqueror’ (r. 1066-1087)” The Royal Family. https://www.royal.uk/william-the-conqueror. Accessed 26 November 2018.

15. “William I ‘The Conqueror’ (r. 1066-1087)” The Royal Family. https://www.royal.uk/william-the-conqueror. Accessed 26 November 2018.

16. Eric, John. “Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession.” The English Historical Review., vol. 94, no. 371, 1979, pp. 251

17. Winkler, Emily A. “The Norman Conquest of the Classical Past: William of Poitiers, Language and History.” Journal of Medieval History, vol. 42, no. 4, 2016, pp. 467.

18. Eric, John. “Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession.” The English Historical Review., vol. 94, no. 371, 1979, pp. 255

19. Robinson, Mark. “How the Normans changed the history of Europe.” Youtube, uploaded TED-Ed, 9 August 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Owf5Uq4oFps. Accessed 4 Dec. 2018.

20. Johnson, Ben. “The Norman Conquest of England.” Historic UK. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

21. Castelow, Ellen. “The Battle of Stamford Bridge, 1066.” Historic UK. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

22. Castelow, Ellen. “The Battle of Stamford Bridge, 1066.” Historic UK. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

23. “William I ‘The Conqueror’ (r. 1066-1087)” The Royal Family. https://www.royal.uk/william-the-conqueror. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

24. “William I ‘The Conqueror’ (r. 1066-1087)” The Royal Family. https://www.royal.uk/william-the-conqueror. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

25. Johnson, Ben. “The Norman Conquest of England.” Historic UK. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

26. Eric, John. “Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession.” The English Historical Review., vol. 94, no. 371, 1979, pp. 253

27. “William I ‘The Conqueror’ (r. 1066-1087)” The Royal Family. https://www.royal.uk/william-the-conqueror. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

28. Creed, Robert P. “The Norman Conquest and the English Language.” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 304, no. 5675, 2004, p. 1243.

29. “William I ‘The Conqueror’ (r. 1066-1087)” The Royal Family. https://www.royal.uk/william-the-conqueror. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

30. Johnson, Ben. “The Domesday Book.” Historic UK. Accessed 26 November 2018.

31. “Hundred Years’ War.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed 9 Dec. 2018.

32. “Hundred Years’ War.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed 9 Dec. 2018.

33. Hunt, Alex and Wheeler, Brian. “Brexit: All you need to know about the UK leaving the EU.” BBC News, 5 Dec. 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-32810887. Accessed 9 Dec. 2018.